A glimpse into the subcontinent’s sartorial journey—from draping to shaping textile as second skin—where dress evolved as both art and adaptation.

In the earliest rhythms of South Asian life, clothing meant drape and fold. The unstitched garment, from redda, dhoti, saree, ohoriya to uttariya, flowed around the body with intimate knowledge of human contour and gesture. But cloth, like culture, responds to pressure and passage. As South Asia shifted through major migrations, complex social and caste hierarchies, trade winds, and colonization, the region’s clothing changed too. This is how stitched garments that follow the body as a second skin were shaped by the practicalities of time and work.

Clothing as a Mirror of Politics, Climate, and Livelihoods

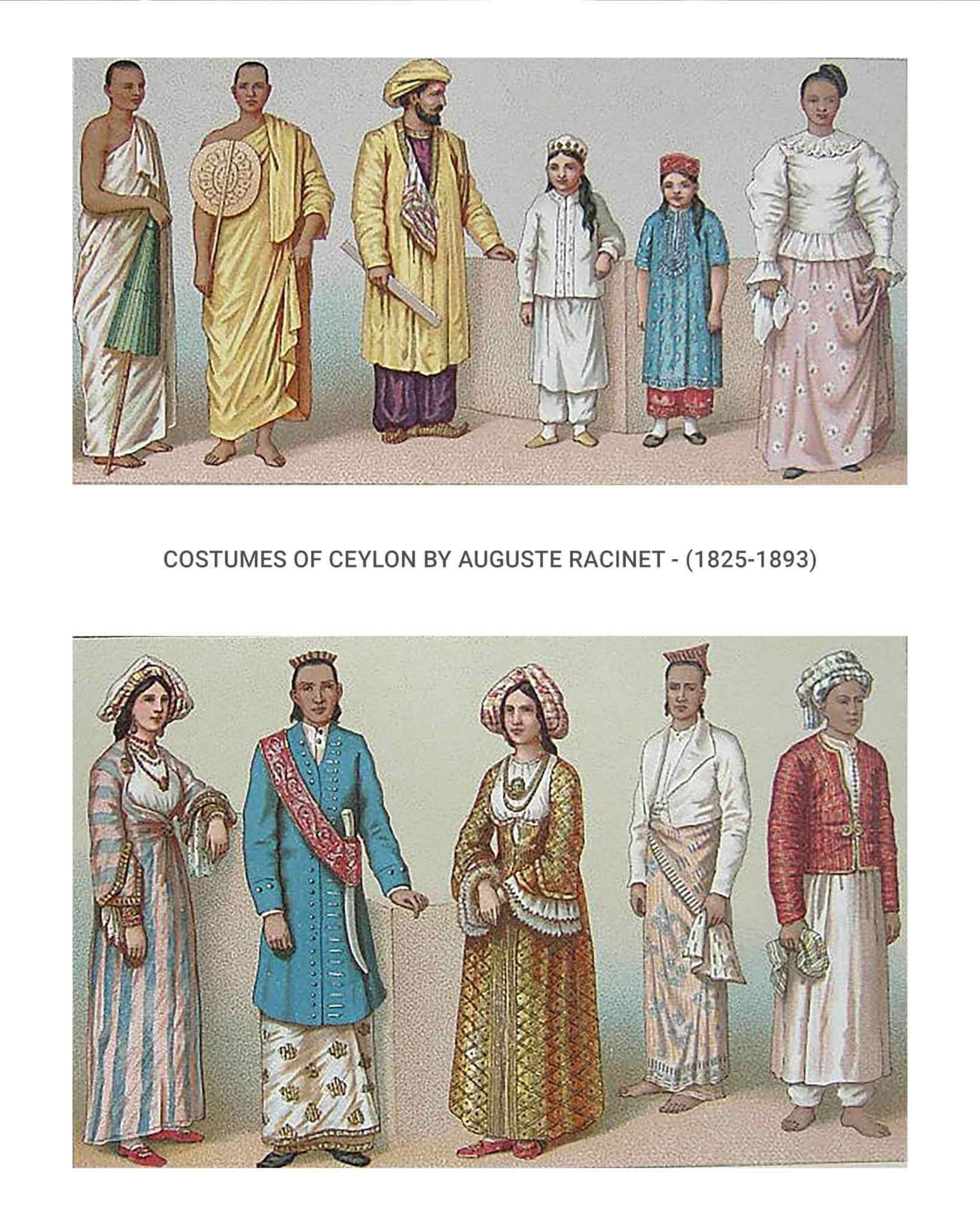

In Sri Lanka and India, pre-colonial attire was unconstructed and minimal, rooted in ease and openness. Even among nobility, clothing followed the ancient model of antariya (lower cloth) and uttariya (upper wrap).

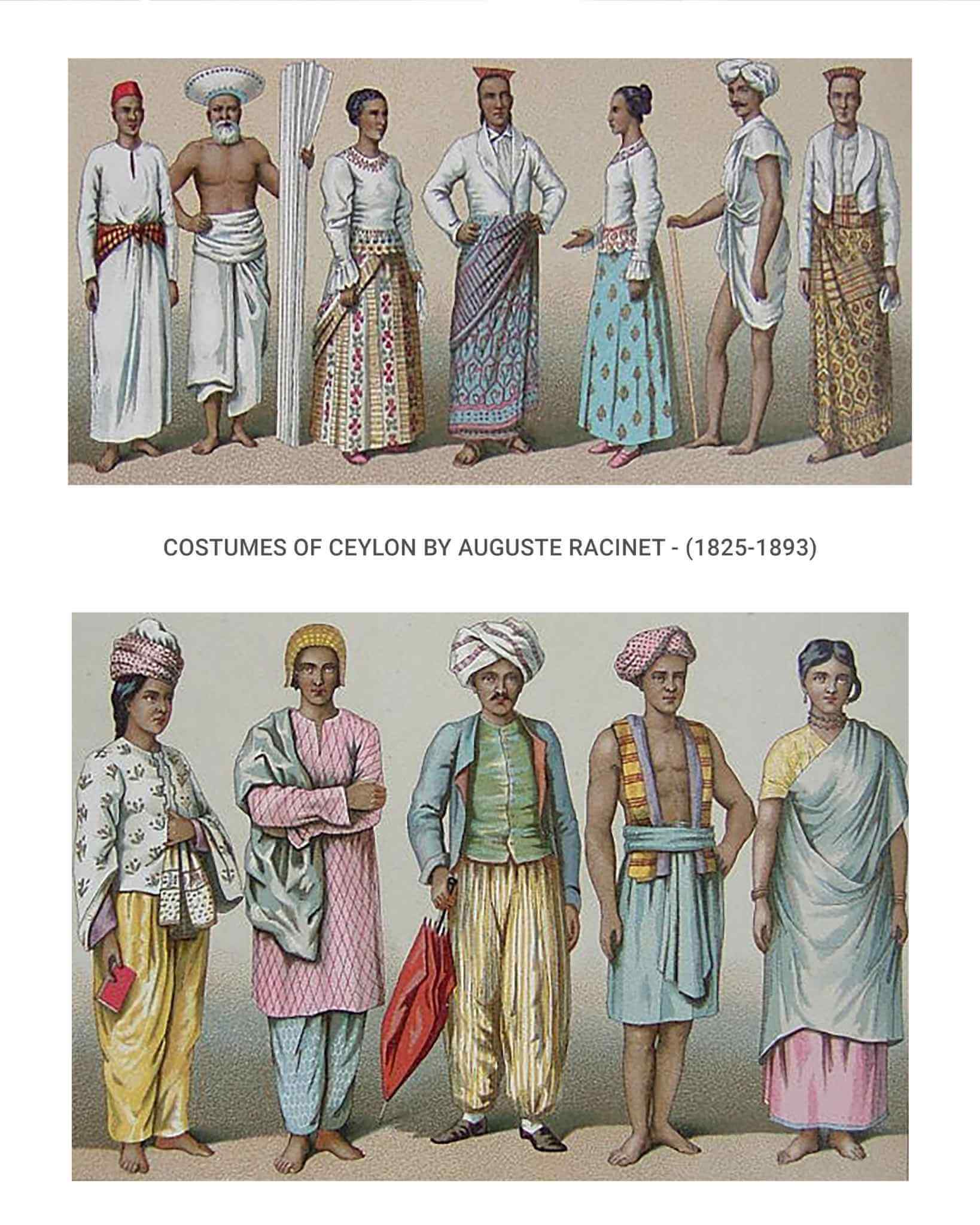

Stitched garments emerged from a heightened need for functionality. Soldiers, messengers, and dancers needed clothing that would not loosen or unravel mid-motion. In early South Indian kingdoms like the Satavahanas, sculptures depict tight-sleeved tunics worn with fitted trousers—signs that stitch emerged where movement demanded structure.

In Central and North India, the arrival of the Kushans brought long coats, buttoned tunics, and layered ensembles. Over time, stitched forms appeared alongside draped ones. Gupta-era murals at Ajanta show royalty still clothed in flowing cloths, while attendants, entertainers, and soldiers appear in stitched blouses and tunics.

The thread of stitch continued. Under Ghaznavid and Mughal influence, stitched robes, coats, and tunics gained detail—lining, embroidery, and collar work. Garments became both symbolic and practical—robes of honour, coats of power, clothes of climate.

In Sri Lanka, stitched garments emerged slowly, adaptively. The kabāya—a top garment worn by both men and women—was one of the island’s earliest stitched forms. Open-fronted and made in both fine cotton and animal skin-lined varieties, it responded to climate: airy for coastal heat, heavier for the central highlands. The simple stitched shirt, kamīsa, introduced through trade and colonial contact, evolved from the Arabic quamisa and Portuguese camisa. These shirts appeared in many versions: shoulder-tied, front-buttoned, loose-sleeved. Portuguese presence in Sri Lanka birthed the kabākuruththu—a short blouse that became iconic to the identity of Southern Sri Lankan women. Dutch influence brought in Puritan lace collars and frills, and the integration of ruffled cuffs and hems. Other silhouettes like the oversized bāju hettaya appeared among Kandyan nobility and trickled down to society, often paired with traditional cloth wraps or skirts. These garments stitched together foreign contact and island sensibility, shaping a uniquely Sri Lankan language of dress.

Throughout South Asia, the stitch did not replace the drape; it only added new language to the old verse, bringing a layered meaning to the subcontinent’s attire. It beautifully reflects how hybridity itself is a hallmark of South Asia, where identities are often many-layered, embracing influences from different times and places.

Gender Fluidity in the Universally Human Tunic Form

Across the subcontinent, the tunic emerged as a universal form—known by many names but united in silhouette. The kamīsa, diga hettaya, kurta, jama, kamiz, and angarkha—all belonged to a family of garments worn by both men and women, their shared silhouette reflecting a time when sartorial boundaries were porous. Difference was expressed not in shape, but in textile, colour, embroidery motifs, and occasion.

The angarkha, for instance, was a wrap-style upper garment seen on both royal men and dancers in India. In Sri Lanka, the diga hettaya was donned by royalty as a layer in their elaborate ensembles, and by average citizens when visiting a sacred or respected place like the village temple or an elderly relative’s house for New Year blessings. These garments carried no fixed gender; they followed the body, not its assigned role.

It was only under colonial and Victorian influence that Western ideas of gendered dress became a strict normative in South Asia—cordoning kamīsa, sarongs and trousers for men, and blouses, kabā and skirts for women. What was once fluid and adaptable became codified, and the stitched garments took on more distinct marks of gender.

Exploring Clothing as Chronicle

Evolving from uttariya to blouse, from redda to skirt, was more than a sartorial change—it was a marker of cultural negotiation. It was the body asserting freedom in new terrains of work, ritual, mobility, and self‑expression. For many, stitched clothing allowed both freedom and form: the mobility of trousers, the ease of overlapping sections, the defined dexterity of sleeves were for those who moved between home and work, migrating worlds, seasons, rhythms. Made not to impose shape, but to receive it.

At Rithihi, we see garments as silent chronicles of history, our collective stories. This journey—from drape to stitch—mirrors the adaptation and aspirations of South Asia. It is a narrative that touches on gender, livelihoods, and culture interwoven with the craft of textiles. It reflects how we sought ease, speed, convenience, and identity through what we wear.

So, the next time you explore the collection at Rithihi, view it through the lens of history, as a dialogue on heritage between fluid and form; a visual story of our sartorial cultures and the evolution of South Asia through time.